My husband and I are well matched, with similar tastes in music, literature, and food. We both think a really fun date is taking $20 to a library used book sale and coming home with a big bag of new-to-us books. So when he recommended a book many years ago, I read it.

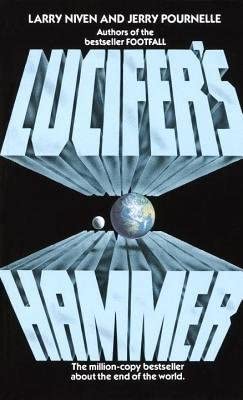

The book was Lucifer’s Hammer, a science fiction drama in which survivors of an earth changing event band together and each brings important skills to the struggling collective. Only those with skills that are deemed necessary are afforded the safety of the sanctuary. The others are left to fend for themselves.

It hit me harder than most fiction, and I wondered what skills I had or could develop that would gain me entry to the safe zone in the event of a similar disaster.

At the time I read Lucifer’s Hammer, I was doing a lot of handweaving and reading about fiber arts, and knew that I knew how to construct a loom, spin yarn, weave cloth, use natural dyes, draft a pattern, sew clothes, and make rope—starting from scratch with simple tools. I reckoned that everyone would still want and need clothes, and that might be my entry ticket to the safety and provisions of the group compound.

As the years went by, I found myself thinking about the plot from time to time, and when I developed a new skill, I would wonder if and how it was going to be needed in times of disaster. I’d think, “Fun, but will it get me into the “Valley” when times are really bad?” Most things were just fun and not truly useful.

I thought learning about growing food or rearing poultry would be another good thing to add to my disaster resume, but didn’t really think those skills would be rare and needed, since everybody we knew at the time had a rock star level tomato and zucchini garden. Another avenue, one more attractive to me, was learning the secrets of wild growing plants—which ones were edible, which ones were poisonous, and which were useful for fibers, medicine, and tools. Foraging would definitely be a useful skill for the end of the world as we knew it.

Most of those book sale bags from our best date nights had at least one book about plants in them, and I tucked away knowledge tidbits from those non-fiction finds whenever I had spare time.

More recently, the internet has afforded cool study opportunities and new virtual communities to learn from—some wonderful, and some a little freewheeling and scary.

I’ve been thinking for years that just knowing about foraging for food isn’t enough. It would definitely take some practice to be able to do it efficiently enough to really feed your family if all the wheels fall off the bus. When Covid-19 broke out in China a few months ago, I could see that the situation was definitely going to get out of hand sooner or later. I’m not saying we are going to lose civilization and grocery stores as we know them, but it’s been a good reminder that we are not promised stability in this life. Other disasters could be much, much worse. What better time than now to get ready for whatever comes?

I reviewed a few books on foraging I had in stock and made mental notes about where to find some of those plants on our refuge and around the neighborhood. My daughter and I annotated a beginner’s foraging book for her neighborhood. She’s fortunate. Most of her lawn weeds are edible. I spent some time thinking about strategies too. It was unlikely I’d be able to physically compete with the neighborhood’s biggest guys for those terribly obvious pecans lying around on the ground, but I might know about some things they didn’t know were edible and wouldn’t want.

At any rate, it seemed a good time to practice what I’d been learning about for so long. Knowing all about how to woodwork is not the same as being a capable woodworker. I felt like foraging for food was the same and needed to be practiced to be useful, so decided to give a few things a try while grocery shopping is still available and there’s no real pressure.

So far, we’ve had five dishes that included some wild foraged ingredients. I’d say they were all successful, and helped keep us from having to grocery shop.

CLEAVERS ( Galium aparine) We used Cleavers for a cool green tea. Books assure me they are nutrition packed. The tea looked a lot like an ordinary green tea, but was not caffeinated. It tasted light and slightly “green”. The little Velcro-like hooks on the stems seem unappealing to eat raw, so we didn’t try that. Cleavers had a good year this year, and there are patches in weedy areas of the yard as well as at the farm. They love all the rain we’ve had.

WILD LETTUCE: (Lactuca serriola) Before you even think it, this is not the wild lettuce with hallucinogenic properties. That one is only found in the US as escapees in a few places in California (Anyone surprised?). This one made a nice addition to my family’s traditional Italian comfort food, a dish the kids dubbed Beanie Greenie when they were little. Kidney beans, pasta, greens, olive oil, onion, salt and pepper combine to make a dish that’s both filling and nutritious. Something about it calms me when I’m stressed. For extra richness you can add butter or chicken broth. Only a few upper leaves from each plant were used, as the larger lower leaves become bitter. As a bonus, all these plants needed weeding out of my home landscape anyway, so we accomplished two things by eating them.

CORN SALAD: ( Valerianella sp) This delightful spring green has a light nutty flavor that combines well with other greens and vegetables. We used ours in salads. Surprisingly, these small annual plants hold quite well after harvesting if they are kept moist in the refrigerator with their roots still on. A week later, they still looked like they were freshly picked. We ate only the upper halves where the leaves were tender, but I pondered the possibility of replanting the lower halves since the roots still looked good and firm. In the end, I didn’t replant them, because this year was an incredible year for this plant, and it carpeted whole swaths of the farm. I didn’t need to feel guilty about using some from my own property and not replacing it. There was plenty for us and for every creature that lives there.

WILD ONIONS: (Allium canadense var. canadense) The bizarre tops of Wild Onions are just as edible as the leaves and bulbs are. They are clones of the parent plant, and are tiny bulbs, ready to drop off and start growing where they land. In this case, I opted to harvest the tops only. I have a patch in the yard that is trying to take over the world, and eating the tops off keeps the little bulbs on top from sprouting into new plants. I don’t want to eliminate them—just control them. Raw, all parts of the plant are quite pungent and may taste too strong to be enjoyable. Cooked, the flavor mellows, and we used our batch to make a nice potato frittata, sautéing the onions first.

GREENBRIARS: (Smilax spp.) I took a little break from a plant rescue dig this week to harvest a few Greenbriar shoots. The shoots are harvested by bending the supple tips of the Greenbriar plants and only taking the part that snaps off easily. The very tips that break off are crisp and clean tasting, like a really good Romaine lettuce in flavor. The thorns aren’t stiff on the tender ends, and don’t scratch at all. I love snacking on them raw while I’m hiking. I’m told the vitamin profile is much like Asparagus, and the protein content of these growing points is also high. There’s so much Vitamin K in Greenbriar shoots, that people on blood thinners are advised not to eat them. Vitamin K promotes clotting. Deer love these shoots too, and the high protein content does them some good. My family ate these when I was a kid, and I stuck with Mom’s old recipe plan. Once harvested, a light steaming in salted water and a vinaigrette dressing is all they need. We ate them hot a couple days ago, and ate the cooled pickled leftovers cut into a salad today. The nice thing about these is that they are super easy to harvest. It took less than five minutes to gather two meals’ worth at the edge of the wild woods.

We’ll continue to practice a little minor foraging while the pressure is still off, but looking down the road a few years at the possibility of retirement, I’m thinking it’s also a great way to trim the food bill in our senior years, and it’s time to get serious about learning the craft–not just collecting book knowledge, but the putting the knowledge into practice so we can do it if and when we have to.

Soon it will be blackberry season, and if the weather doesn’t do something terrible like turning hot and unrelentingly dry ( I think I just heard Texas say, “Hold my beer!”), there should be a magnificent crop this year. Blackberries and Dewberries (both Rubus species anyway) are a no-brainer. Who wouldn’t want to harvest those tasty morsels of vitamin packed goodness? I can almost taste that “essence of summer” now.